Mong-Lan

I

When I picked up the Best American Poetry edition of 2002, edited by Robert Creeley, I was expecting the contents to be heavily indebted to his own works and those of Charles Olson. Creeley had always been aware of his literary legacy and outspoken concerning poets, whether in favor or disapproval. I was happy to find that while the book contained poetry that I can understand him appreciating, he did a fine job at sifting through imitators of his style and finding new, exciting voices among those writing with a debt to himself, Olson and Williams. The poem "Trail" by Mong-Lan stood out in my mind as unusually moving. She writes in a style which conjures the poets already mentioned, but writes also from her post in contemporary culture and from an entirely different generation, one dealing with the detachment and freedom of technology, the banality and distance of modern travel, and with the politics of emerging globalism. Still, she stays true to an ethos of working toward the truth of the "thing being seen," vividly describing scenes with a chacteristic, fluid line. Trails tells quite a lot about Mong-Lan's personal history, even without having to spell anything too broadly-it was clear that she was from Vietnam but no longer lived there, that she was forced to move and was still emotionally focused upon Vietnamese life, and that her way of understanding the world was often a visual one. I was not surprised, upon looking her up on the web, that she was a painter and photographer before a poet (at least, professionally), and left Vietnam at a young age, living a somewhat gypsey life with her parents before settling in Houston, Texas.

Since then she has become one of the most interesting and important poets I have read in recent memory, a young master who can broadly examine culture from her place as both exile and insider. What emerges is neither shrill nor sleepy, but lyrical and attentive to the weight of experience, observing as "children play mindlessly in satellite/ shores" and "men pick at French-laid concrete like crows// shovels and picks at shoulders." Her importance comes from how she bestows importance on the act of seeing, and the aesthetic heights she reaches in her descriptions via careful attention. Reading her descriptions of Vietnam were so fresh that I felt the importance of each detached instance with greater weight than I experience in my usual daily routines. Her poetry draws its greatest strength from the vividness she conveys through a strategy of fragmentation similar to the variable foot of WCW's poetry. The fragmentation and industrialization of the line envisioned by WCW has grown more appropriate with time, and seems especially well used by Mong-Lan. Her breaking apart of the line across the page combines the sense of line-break as scoring, which it does sometimes to humorous, musical or explosive effect, as well as sometimes being simply for the visual impact of the page. Either way, it improves the allure of her work. It is interesting that Williams tried to make a distinctly American poetry. That Mong-Lan writes in such a western style makes her even more ground, and her work even more important. just as Salman Rushdie may be one of the most important writers about cultural exile, since the modern novel is a particurlarly western event, so Mong-Lan can write about the contrapuntal snare even as she writes from "this age our era i can correctly say this an era of exile"

Also Williams before her, Mong-Lan ultimately owes a debt to Sappho, of whom fragment 16 could be a possible inspiration for Trails:

These — cavalry, others — infantry

others yet, navies, upon the black earth

hold most beautiful. But I, whatever

you desire.

To make this clear to anyone

is most easy.

In Mong-Lan's book Song of the Cicadas she has a poem called A New Vietnam. In this poem she envisions the state of Vietnam, whose cities are growing quickly, and whose people feels the growing pains of that expansion. The second of this three-part poem focuses on the Hue people of rural Vietnam, who face danger in their fields still from an American presence in the form of unexploded ordinances. Indeed, war and the American presence is a major element of this new Vietnam, one in which urban skyscrapers are becoming more common even as rural communities struggle with the past and with a decaying sense of culture, a Vietnam that is both conflicted and eternal:

honey-moon light swoops over the valleys

upon the Da Lat mountains

like squadrons

Never staying on one image for long, she jumps from the moon light resembling plane formations to a banana vendor who criticizes her for scrutinizing his crops. Many of her poems have this sort of humor in them, which comes from her intense closeness to real life. In an Robert Creeley interview conducted by Mong-Lan, he mentions that "insofar as "the poet thinks with his poem," as Williams put it, humor will be a factor." One gets this feeling with Mong-Lan, that as her images jump and shape-shift on the page, that she is undergoing a sort of process of realization through opening herself to memory.

II On "Trail"

Of the Mong-Lan poems I have read, I return most often to that first poem of hers I read, Trail. It is an eleven-part poem (including a ten parts and a prelude) in the form of a letter to a lover far away, who is spoken to directly only in asides sighed throughout the parts. The poem functions on several levels, another important level being the travelogue. Traveling and recording one's travels informs her progression of memory and involves themes such as photography, landscape and indigenous cultures. In order to work through her memories and give them a shape which is meaningful to her, she sometimes will linger "through woods red with evening of dreams spilling" and sometimes more quickly; "to accelerate time I walk from arizona to new york to/ viet nam."

The trail, that record of her travels and of others who have traveled with her informs the piece. She writes;

on this trail of a thousand years there is us amidst misfits & assiduous trees

we have walked

over sand sick with evening of words spilling

what is the remedy for momentum for mania a deciduous heart?

The observations concerning trees are a major theme in the poem, assiduous/deciduous, opening the physical world up to her dilema of time and timelessness without succumbing to the pathetic fallacy.

The desert is mentioned several times in relation to time passing. The eternity of desert lurks around the edges of the poem, surrounding it but never able to be seen for long. As a visual allusion to eternity it is conataminated by the eye, as the "desert raging on a contact sheet the outbreak of pneumonia" or the "satiny desert/....sand sick with evening...." It is possible, given her use of phrases, that she means to observe the sand as sick with evening in the sense that the pattern of living and experiencing time is a sickness suffered by inanimata, or it is stricken with living. Later she recalls the desert again with the observation that "shimmering water copies the blazing desert," maintaining again the primacy of desert to that of water. What can we learn from this series of remarks? It is interesting that the trail does indeed venture near the desert, "dryness & trails," but the poem never goes deep into the desert. Mong-Lan is aware of it as an analogy for beginnings, for tabula rasa. The satiny desert that begins this poem points to a landscape of birth, even as a the "scandent mountains" which begin to cover our view join Mong-Lan's conception of time at the end of the poem. Even on a trail thousands of years old, we are young compared to the mountains which have "had a million years to practice their lines."

The desert is a model as well for this world we live in, a sick world, a global world, an "era of exile." It is the era of the satiny desert as well, and of the sick sands, because this desert that waits for form is both the metaphoric present of an exile culture with no roots, or whose roots are mangled beyond repair, as well as apocalyptic vision for the future, where technology and cultural clashes have raged out of control, or in the case of the amazon rain forest, which she explicitly mentions. In the sixth part of Trails Mong-Lan writes that she dreams "of sand dunes flying ridges & sun i dream of wind blowing darkly usurping/ cultural designs...."

Contemporary culture is a major element of what makes Mong-Lan's poetry interesting. Another factor to this fragmentation is the quick-jump of her ideas and images from place to place, which seems more appropriate to our culture today, and makes Robert Frost look that much older, given our "hyper-awareness born of technology a silver butterfly heavy/ inside this drift split." As is constant in this poem, one image preludes or echoes another. In this case we are drawn back to the poem's prelude, when even as she recalls being at the ocean with her lover, "past we touch/ inside our skin a sterling sound." Time in this poem passes by with the power of narrative, that we will it to pass however imperfectly, and are ourselves contaminants in this sense. It is these elements of change within the author, who may hear a sound and then specify what she believes that sound to be as it occurs to her later, which constitute the narrative power of the poem, giving the poem a sense of time and subsequent life of its own.

The hyper-awareness poses a mixed blessing. It allows her to travel and call her lover, but laments that the phone is but a machine that "keeps us a-/ part/ how many digits is in the number/ for consciousness the total of God?" While the breaking apart a-part may be a bit gimmicky, it does follow with what is throughout her work an interest in voicing language closer to the physical event of speech and away from language as a formalistic process through which it is parsed and organized with periods and capitalization. In the twenty-first century, this tactic is a bit of a high-wire act, with the freedom to voice poems of a fantastically informal nature being long-ago accomplished and since become passe, but she usually pulls it off. When she writes:

grotto of swimming bats I do not swallow

the darkness rocks under my feet

are piranhas' mouths if I miss a step

stalagmite meeting stalactites coincidences

taking forever to form

It is difficult to imagine her usuing proper punctuation. When she maintains a fluidity to her writing, which is established by her rhythm, her lack of punctuation falls right into place.

One of the best images presented in Trails is that of an automobile at night, which reminds me of a Gary Snyder poem in which the headlights of cars contain their own calligraphy. For Mong-Lan, the cars allude to her way of experiencing as a poet, only seen in a strange object that may or may not see her, as she "see cars pass & wonder if the headlights expose & wonder if any will stop."

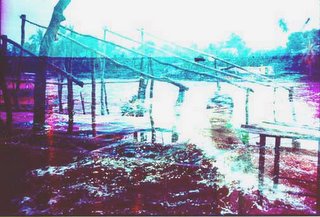

The car assumes an allusion to the poet, the road memory and headlights the poetic eye, seeing without positing preconceived notion. This poetic process is balanced by our humaness, which is not purely poetic, and steers the vehicle. Mong-Lan observes the world in its cultural entropy but allows for the pain and injustice to speak for itself. These memories is usually assumed in that the poems are often written in present tense, which serves to intensify the patchwork, collage-like assemblies that Mong-Lan creates, both on the page with words and on the canvas with paints. She also uses photography, and in all of these mediums there is a constant use of multiple-imaging, such as pictures placed atop other pictures. In her poems we are frequently confronted with this technique of multiplication, or juxtaposition, which creates the illusion of a different whole from several sources. The overlap is especially resonant for a poetry of exile, where Mong-Lan writes as a Vietnamese/American, seeing the world as what it is and what it has been, and in seeing them both as one, perhaps glimpsing the future.

All Photographs by Mong-Lan. These along with pics of her paintings as well as a few of her poems and her excellent interview with Robert Creeley are available at her website, www.monglan.com.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home