“It works on its own terms. It puts you on the spot. It asks of you the fear and courage that it asks of its subject."

-Greil Marcus

I've been listening to the Pixies for the first time, in earnest, in a few years. The Greil Marcus quote above regards something else entirely, but seemed apt to how the Pixies music seems to me. Their music has been couched in the back of mind, and heard in the echolalia of many bands I've been listening to in the meantime, such as Modest Mouse or The Arcade Fire. I'm struck, listening to Bossanova, how many bands owe subtle debts, not only to a formula that can be written out in terms of chords, abrupt transitions, etc, but by the aesthetic quality of estrangement and particularity that characterizes their work.

For my money, Bossanova is the strongest Pixies album; it doesn't have the hits of Doolittle and Surfer Rosa, but it is the most comprehensive statement that they made, perhaps because of the shift of songwriting duties squarely to Black rather than Black/Deal, and it holds up to more listens that I know. Surfer Rosa's grittiness is more fun than anything on Bossanova, but the songs themselves are not as strong; Trompe le Monde has a few great songs, but also a few omens of the spotty Frank Black career that would follow, splitting the seam of the songs apart between rock-a-billy and prog; Doolitte holds together more as a collection of singles than as an album; Come On Pilgrim offers songs less fully formed and under-produced. The spacey ambiance of Bossanova worked best for the Pixies, as producer Gil Norton brought out on the deep snare drum, reverbed backup vocals and guitars. I would have sworn by memory there was a theramin on this album, but I can't hear it anywhere. The sound lends a more subdued tone than other Pixies albums, and manages to contain the shrieking energy of their songs without dampening them. This effect creates the illusion of distance, much like the Pixies logo orbiting the planet on the front and back covers of Bossanova. A little distance is good, because there is a lot in this album which seems clearer than other Pixies albums by virtue of a little space.

So the album sounds good and is perhaps more listenable as an entire album that anything else the Pixies put out, and that forms half of my idea of what makes it a good album, the other half being the ideas and culture surrounding the album. It feels strange to talk about culture regarding an album, and a band, so dedicated to surrealism, yet I can't help thinking of it when I remember seeing them in 2004. The crowd, which I expected to be made up of aging hipsters, was largely people younger than myself, teens and pre-teens, and people I would likely expect to see at a Fall Out Boy concert. Pixies have been moved into the mainstream by strange chance, that the 4AD label manager's girlfriend liked their demo, from their influences in marginal icons like Husker Du, Pere Ubu and surf rockers into being torchbearers, however impish.

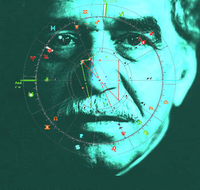

Pixies albums seem to exist outside of cultural contexts in the sense the Public Enemy seemed defined by them. While Chuck D might speak to specific political issues, Black's lyrics describe women in holes, beaches near imagined future houses, and asks how lemur skin reflects the sea. There are few references to a broader cultural landscape or understanding, but rather a seemingly random array of particular objects. The cover echoes this particularity; a disembodied clump of hair lies upon velvet sheets on the back cover, located inside as screen print, located over an overexposed and obscured picture. The layers in Bossanova work this way, objects, figures of speach and narrative intentions seem severed, and presented. It leaves one wondering where these snipets of lyrics have been in Black Francis's mind, and why exactly he wants to know about the lemur skin. But we can't know, and that is the point, we can only appreciate the juxtaposed beauty and terror of reorganizing these meaningless objects into a new subjective experience. The album begins with a cover of the Surftones' "Celia Ann," one of several songs named after women on the album, which plays with the idea of influence. It serves as yet another found object, picked up and subjectified.

The term Bossanova is another example; it is a type of music, none of which is to be found on this album. The word seems disembodied, sung only in "Hangwire" in a menacing offer/threat: "Every morning and every day, I'll Bossa Nova with you." The term of course means "New Way," a new understanding of familiar objects, torn from traditional understanding in surrealistic fashion. Even the name of the band was picked at random from the dictionary.

The transposition of objects is easy. There are surrealist parlor games people can play that are always a drag. Punks had been using the bricolage technique of overlaying familiar objects to create dissonance since the seventies. Black Francis is concerned with this, however, and the lyrics are not tossed off gestures, but rather a inquisition into how this process works. The song "Digging for Fire" is concerned with this. The characters themselves, who speak the chorus and message of the sons, are random, anonymous, aged people who live "down the road" and "on a beach near a house where I am going to live." The settings are immediate yet utterly subjective. The woman digging a hole mirrors the next song, "Down in a Well," in the sense of a reversed face of elements, water & fire, and shows the way image and interest work in Pixies songs; often as tropes, connected loosely or merely apparently.

If there is a centerpiece to the album it might be "Rock Music." The song offers a cornerstone to the album which other Pixies albums lacked; it is not only a good song, it maps out the possibility of their vision in a way that all other songs on the album run through it. It is notably first for its bold title; not only absurdly simplisitic, but evocative given the album's purpose in severing, even mutilating objects. The Pixies are trying to define this thing, sever it, reorganize it. Rock music has to be killed and brought back to life, as they say, and that is an important thing the Pixies do here. And what are the lyrics? Like the house where he is going to live, they are lyrics which he is trying to say. Incomprhensible, and absent from the liner notes of the album, the phonemes Black belts out only sketch a space where lyrics should be.

There is ultimately a childishness in this, a part of us that could actually believe in pixies; in other words, that dreams. "I tried to say/ Even in my dreams/ Words get blown away," laments Black. The album, and the Pixies themselves, suceed on these quick-silver terms; their vision of mutable subjectivity and violence of shifting perception harken back to the Dali's razor-blade introduction to "Un Chien Andalou." Another sensational pop artists, Dali described his own work as "terrifying and edible," and the same goes for the Pixies.